The haufbraus of San Francisco

This is not the typical story of haufbraus that many a local newspaper have covered, this is a bit deeper!

If you take the 38 down Geary on the corner of Van Ness you would be hard-pressed to not notice a strange blue building placard with mid-century signage: Tommy’s Joynt.

A favorite hangout spot of Metallica and purveyor of meats and breads aplenty, one could be mystified by its unique atmosphere and election surrounded by modern glass facades and Ikea laced interiors of neighboring buildings and restaurants. What makes this restaurant also unique, is that it's primary descriptor is not "beerhaul" or "meat palace", but "haufbrau" or "hauf-brau".

The word itself "haufbrau" is German, but the concept of a "haufbrau" appears to be endemic to California, particularly the Bay Area, where at an era from the 1960s to 80s one could go up to someone and ask them if they ate at a haufbrau and you wouldn’t get a confused look.

A haufbrau was a place where you could dine in, pick some meats cut up at a counter cafeteria-stye and grab some beers with buds. A beerhall with meat is not unique, but it being a cafeteria and having such a specific german name tied to it brings me the question:

Why call it a haufbrau? why did this concept take off in the Bay Area specifically?

Yes, it's german

Long ago, 300 years before America was even founded, the kingdom of Bavaria had established the Hofbräuhaus, a state run brewery. The brewery itself had gained prestige and notoriety for its beers, Bavaria itself was known at least Europe-wide for its brews.

Notable buildings, like the Haufbrauhaus or the Taj Mahal end up becoming placenames for their culture association in foreign land. We do see a lot of Taj Mahal restaurants everywhere you go, no? And it does have to do with food, meat on a plate, with beers; simple enough right?

Coming to America

In 1867, a John Iffland had imagined bringing his own Hofbräuhaus to America, and opened it over in Newark, NJ. Unlike the 1950s “hofbrau”, it was very much a standard restaurant, serving German food like beef and beer catering to the German businessmen visiting the region.

The german diaspora up to this point in America in the 1850s were often religious refugees of protestant origin that settled in the hinterland; generally out of the eye of the american zeitgeist, but ensuing instability in Europe and rapid industrialization and commerce of Germany had brought a new urban breed into American cities; some ending up even on the west coast.

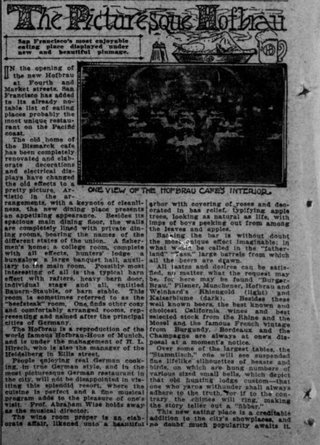

One of those immigrants was Heinrich “Henry” Hirsch, an entrepreneur from Hanover who opened the Heidelberg Inn, one of the first new restaurants that emerged from the ashes of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The restaurant quickly became very popular, allowing Hirsch to open his magnum opus restaurant, the Hofbrau, in late 1912.

The Hofbrau, was similar to the Heidelberg Inn and the Hofbräuhaus’ before it; selling German food and beer to much fanfare. Unfortunately its fame for selling German fare would come to be it’s undo it in the coming years; as for the onset of World War 1 and subsequent American involvement against the German people had put a crosshair on the Hofbrau’s back.

The Hofbrau wasn’t the only Hofbrau in the Bay Area, there was another hofbrau located in Oakland that had a cabaret, the two were confused so much that advertisements for the San Francisco Hofbrau always included that they didn’t have cabarets.

Anti-german sentiment quickly rose in America after the onslaught of the Great War, the Hofbrau was not shielded by its popularity. The restaurant and many other German establishments had become targets of violence by mobs who had grown to hate all things German.

For Heinrich and many others like him, they had to essentially force themselves into assimilation, to give up their history and culture into the mostly Angolcentric American world at the time. Heinrich became Henry, and the Hofbrau became the States restaurant [1]. A Native American themed restaurant that served essentially the same food, though now framed to be American; so American it was Native American!

Garbed in ceremonial robes, in the presence of their awe-struck but approving tribesmen, chiefs of the Navajo, Papago, Apache and Hopi Indians last week formally renounced forever the symbol that has adorned their baskets, pottery and temples for centuries—the swastika. This they did on the reasoning that Nazi Germany has desecrated the symbol by acts of aggression and persecution.

To many, familiar with the history of the swastika, its abandonment by the tribes may seem pointless and a little absurd. It is one of the most ancient of decorative and symbolic emblems, found embedded in the mosaics and temples of the Greeks and Egyptians—and amazed white men discovered it, a mystic, hallowed symbol, among sun-worshipping Incas and other American Indian people.

Yet the white man shouldn't smile too broadly at those serious Indians. All save youngsters remember, with an inward blush, that in the World War we Americans abolished the German language from public schools, band leaders ceased playing the glorious music of German composers—many of whom were long dead and had never heard of the Kaiser and militarism. American restaurants didn't serve 'hamburger'—although it was all right to eat the identical dish under the label of 'liberty steak.' One famous San Francisco restaurant, the Hofbrau, was saved from mob wreckage only by the presence of mind of the orchestra leader, who swung into the Star-Spangled Banner and so obliged the mob to stand at attention until the cops arrived. The restaurant continued to operate in safety by the simple device of changing its name from the Hofbrau to The States restaurant.

That type of reasonless emotion may easily become as dangerous as it is ridiculous. Most of Europe is on such an emotional jag of murderous malice today. Jews—not individual Jews who might be guilty of offenses—but all Jews, are despoiled, insulted, killed, simply because they are Jews. The mere racial label 'Jew' is a special symbol of unreasoning loathing, to Hitler and his immediate followers.

More than ever, in these times, when blind hate is engulfing reason and understanding and tolerance on every continent but this one, Americans must hold resolutely to the common sense and sanity that are the hallmarks of civilization itself.

No, we have little room to laugh at the Indians turning thumbs down on their own ancient symbol, seemingly defiled. We, in our generation, have been almost equally foolish and bitter. It probably would surprise the Navajo and Apache people to know that another nation, in spite of the regime of hate and oppression which the swastika seems to symbolize today, retains the emblem yet. This is peaceful, inoffensive little Latvia who paints the swastika plainly, bravely, on the wings of its own airplanes.

So became the story of many restaurants like the Hofbrau, hiding away and assimilating over the next few years. Losing interest from the public as German food itself had become more synonymous with standard American faire, hotdogs and hamburgers, saurkraut, etc.

The Hofbrau of San Francisco though had one last go; after an ownership change, the new owners during the interbellum period had put the name Hofbrau back onto the States restaurant to cash in on the name, though eventually the restaurant had also faded away by the second world war, probably due to again, anti-german sentiment.

The cafeteria part

We've gotten a taste of german-american history here, enough to tell us why they sell meat and beer at a place like Haufbrau, but what about the cafeteria part?

Cafeterias it seems were just a big trend, starting in Los Angeles in the turn of the century, to becoming a mainstay afterwards everywhere else. Cafeterias though interestingly enough were on a decline by the mid-century, the automobile and suburbia seemed to pass it in favor of the drive in; fortunately San Francisco was plenty dense to keep this trend alive a bit longer.

Back to the story everyone knows

Now we finally get to 1947, where the first modern "hofbrau" set up shop, Tommy’s Joynt. A cafeteria styled restaurant that served vaguely German food. But if you noticed, they weren’t calling themselves a hofbrau, it seemed to have been applied after the fact, after many restaurants in the following decade followed suit with selling vaguely German cuisine. Restaurants like Harry's Hof Brau in 1954, and Sam’s Hofbrau started applying the word directly into the name, indicating that now this term had a meaning to it, but even the term itself did not become popular in vernacular until the decade after.

It seemed like it was just a perfect alignment of assimilated cuisine with a twist, cafeterias and the desire for something new brought the new name to hofbrau.

So what happened to hofbrau after the 1950s? It kept on chugging along time, switching ownership and losing more and more of its vaguely German roots to an amalgamation of American culture.

One of the more popular hofbrau’s of the time, Lefty O'Doul’s had no semblance of relation to Germany outside of the concept of the meat itself. And as time went on, hofbraus continued to become an amalgamation of America diasporic import, some hofbraus started offering Chinese food, some stopped even being cafeterias.

Today there stands very few restaurants claiming to be hofbraus, the style of dining blended into American culture. Anytime you see a buffet that serves carved meats or a restaurant that have vaguely German vibes, you can see that the Hofbrau is still around.